As someone working in local food systems, hearing news of a whole conference dedicated to food meant only one thing: I had to go along. And with an agenda packed with inspiring and expert speakers grappling with the most pressing issues connected to our food systems, the Right to Food UK Conference on 13 September did not disappoint. The day left me with a clarity around the consequences of a food system that does not serve the needs of our communities, what we should expect instead (and from whom), and how we can achieve the necessary transformations can be achieved.

Framing the issue of food insecurity in the UK

Key food system issues called out in the opening plenaries include the ‘scandal’ of hunger and widespread food bank use: 14 million in the UK today (1 in 6) cannot afford sufficient food while Universal Credit is not enough to meet dietary needs. Children’s’ health was a central piece, with the wider food environment and regional inequalities having a large bearing on whether children are likely to be malnourished or obese (which are two sides of the same coin). It was mentioned that the Right to Food should also mean a right to ‘good’ food: nourishing, sustainably produced, appetising, culturally appropriate and affordable food. And for this to be reflected in pubic food provision, supply-side and consumer-side policies need to match up.

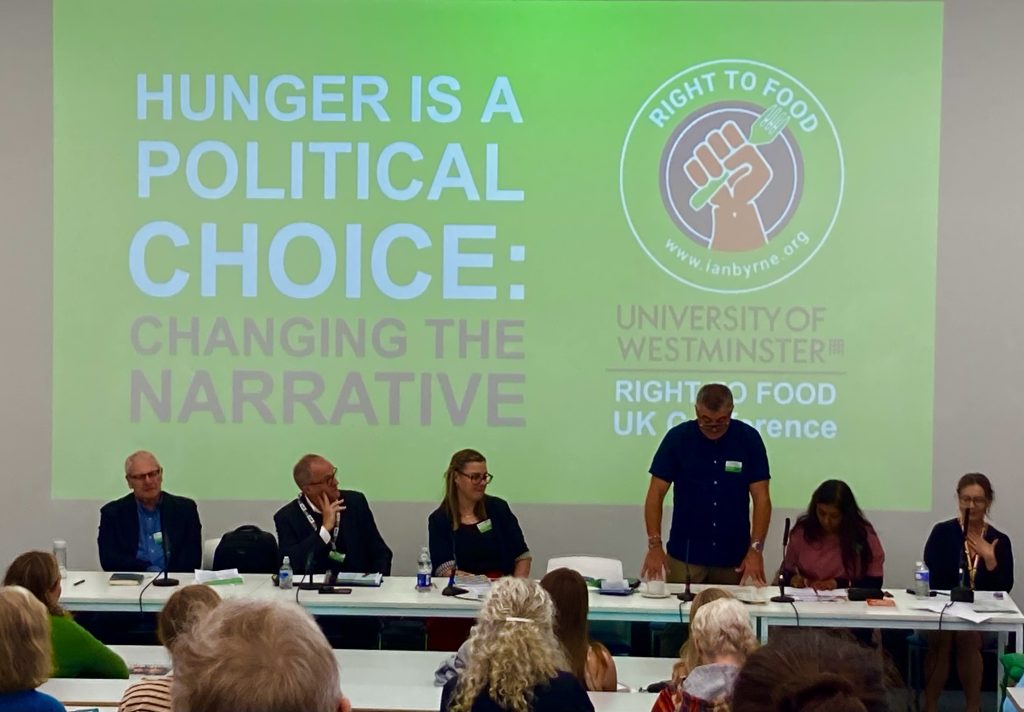

Food security was recognised by London’s Regional Pubic Health Director as a public health issue that ensures health security. It was noted that hunger is a political choice: the UK government has the capacity to tackle food insecurity and dietary-related ill health but is not, meaning that other actors in society are left trying to fill the gap without managing to reach the joined-up approach that is required. Finally, a need for narrative change was noted – one that shifts away from emergency food to long-term solutions that recognise the systemic issues rather than placing blame on individuals.

The conference framed hunger and deprivation as a systemic problem that can be tackled by making access to food a legal right. The Right to Food campaign is spearheaded by Ian Byrne MP, who is now leading a Parliamentary campaign to push its five demands through to law. These are:

- Universal free school meals

- The government to reveal how much money is factored in for food when setting minimum/living wages and benefits

- Independent enforcement of Right to Food legislation

- Provision of community kitchens as a workable solution to food poverty

- To ensure food security through all government policy.

So far, 50 MPs have expressed support, and 25 UK cities have adopted a right to food. The conference sessions delved further into why there is a need for a right to food, and what this could look like, covering food system transformation through social protection, dignity, food sovereignty and food democracy and human rights, building a social movement for the Right to Food, and organising among grassroots and civil society.

Takeaways from sessions

On the topic of food sovereignty and democracy, a Right to Food was put forward as a way to (re)claim food sovereignty, meaning having a voice in our food and where it comes from. This could mean equal rights to water, seeds and participation, and specifically a shift away from industrial food production (which produces 90% of our food) to methods such as agroecology which would seek to meet community needs, care for the soil and embody a different approach to nature whereby we live alongside it, not off it.

Issues of food democracy are tied up with control over land, and power relations between individuals and councils at the local level, which can prevent individuals from establishing the growing spaces needed in a just food economy, or make it so that this is only achievable through remarkable and unpaid efforts by passionate individuals. This needs to change with stronger local food planning to enable community food growing and restrict large corporate interests from junk food outlets through tougher regulations and laws.

Sustainable Food Places was called out as an example of local action focusing on food, and the 120 dedicated Food Officers across the country showing that food deserves to sit as its own issue, not compartmentalsed as a sub-theme of the many other topics that it touches.

It was heartening to hear the interpretation that good food movement is the largest social movement today, if you count all of the people, organisations and initiatives promoting the different aspects of food food.

Suggestions for building a successful movement included:

- Ensure it is inclusive of backgrounds and perspectives while food grows in salience given the rising price of food

- Consider our food culture and what it means to us – should we make more time to sit, share and appreciate food

- Consider where you spend your money as casting your vote

- Free school meals is a campaign that can mobilise support for a Right to Food across political spectrum

- Citizen assemblies as a way to keep local authorities honest

- Look out for Amnesty International’s upcoming right to food standards for the UK

- Ensure that proper conversations are had with food councils

Read more about the inaugural Right to Food conference and the launch of the Right to Food Commission in this article by host of the conference, The University of Westminster: https://www.westminster.ac.uk/news/westminster-hosts-inaugural-right-to-food-uk-conference-in-collaboration-with-ian-byrne-mp-to-tackle-food-poverty